#Yoga #Mindfulness #Brain #Behaviour #Neuropsychiatry

As World Yoga Day 2021 dawns, it could not have come at a more relevant time. For over a year, our world has been gripped within the jaws of a pandemic that comes in waves and disrupts our lives at will. It is a time when much of humanity is paralysed into inaction, by fear of an invisible enemy. Indeed, never before has Yoga and its modern offshoot, mindfulness, been so relevant. When one considers the term Yoga, one often thinks of it as being a physical discipline with mental effects; the adoption of postures in order to achieve a state of mental calmness and equanimity.

Modern science tells us that Yoga is not just about postures and mental states; it has substantive effects on the human brain, indeed effects that one is able to study on dynamic brain imaging such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).

Yoga is one of many important mindfulness traditions, perhaps the most ancient, from across the globe. Yoga which originated in India is derived from the Sanskrit word “Yuj” and means “Union”, indeed a method of spiritual union. In the Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, the ancient and definitive treatise, it follows eight aspects or limbs- yamas (abstinence from immoral behaviour), niyamas (self-discipline), asana (physical postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (sensory withdrawal), dharana (concentration, dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (pure consciousness). Let us focus on the breath, prana, which indeed is the focus of most modern mindfulness practices. Pranayama is the yogic practice of focussing on one’s breath and is meant to elevate “prana Shakti” or “life energies”. To be able “to restrain and control” one’s breathing is a very key element of the pranayama practice which is the fourth of eight limbs in the Ashtanga Yoga mentioned in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Indeed, this focus on the breath is as old as The Buddha who incorporated it into his enlightenment discovery, with little success, at least initially.

And, the focus on the breath is very much part of the modern secular mindfulness practice, techniques such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn, having made it integral practice.

Today, we think of mindfulness as secular, process driven and science based. Yet, Yoga, Tai Chi, the many martial arts traditions in the East, native traditions in the Middle-East, Africa, Latin America and among the “Indian tribes” in North America have incorporated practices that lead to “the thing called mindfulness”. At an extended University of Leiden online course that I attended, the instructor Prof. Chris de Goto described mindfulness “as a consciousness discipline that exists in the interface between science & spirituality, a kind of mental praxis”.

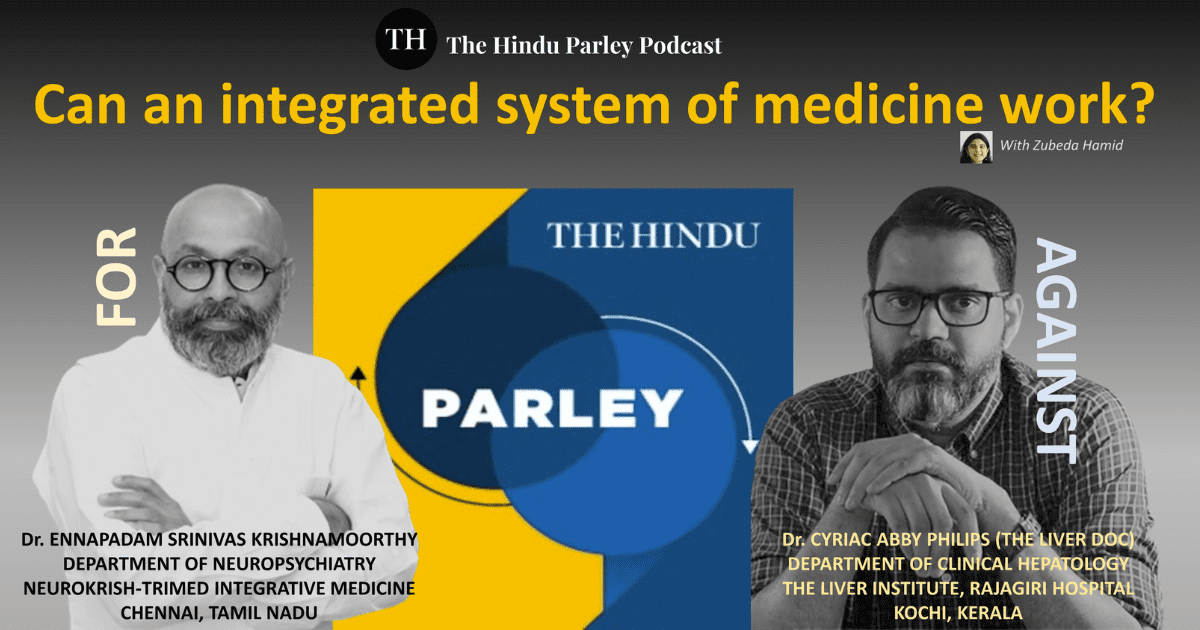

Yoga, therefore, is not just a “body-mind” exercise. Indeed, when things were normal and we medical professionals could meet, we the Buddhi Clinic and Trimed Therapy team had a conclave of experts across disciplines, discussing impact of these traditions on the brain and mind. In that Buddhi immersion, presenting a series of studies about Yoga conducted at NIMHANS, Prof. Gangadhar pointed out that there were positive biological and healthcare (including psychological) outcomes with its practice. Dr. Naveen Vishveshvariah of Yogakshema presented a number of research studies both those in which he was involved and others conducted and published from around the globe, that showed structured yoga practice having impact on a range of molecular, biochemical and neurophysiological parameters under study. In a review in the “Frontiers of Integrative Neuroscience”, van Aalst and colleagues* examined 34 international peer reviewed studies of Yoga using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), or Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), all of which incorporate dynamic brain imaging. They found 11 morphological (structural) and 26 functional studies, including 3 studies that were both structural and functional.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/learning-promise-integrative-medicine-ennapadam-s-krishnamoorthy/

Apart from increased grey matter volumes in the insula and hippocampus, key structures for memory, emotions and behaviour, they were able to demonstrate increased activation in the pre-frontal cortex and functional connectivity changes within the Default Mode Network.

Their findings mirror modern mindfulness research from around the globe, with increasing evidence that mindful states, whatever their origin, have a profound effect on the brain, memory & emotions in particular.

Which then brings us to where the brain-mind -body connection originates from. Behold the Kundalini, that ancient concept of unlimited reserve power seated in the nucleus of every form of existence. Kundalini is conceptualised as being associated with and coiling itself around the bindu (the point of utmost sensitivity); while in its uncoiled, manifested form, it exhibits nada (the continuum of utmost sensitivity). The mystic 3 coils and a half of kundalini are thought to be the basic disposition of kala (the fundamental, the evolvent principle). Kundalini is a cosmic principle; it is seated principally at the “Base Centre” called muladhara.

When aroused the kundalini ascends along the path of Susumna (the yogic channel of life) and is the nature of ejection not projection (what the source loses, the receiver gains).

The susmna and cakras are not thought to be grossly anatomical, in that certain nerve pathways and ganglia are not to be taken as their “physical and physiological basis.” The cakra is considered to be a subtler more potent apparatus, yantram, that controls the economy of our whole being, physical, vital, conscious.

Thus what does Yoga or indeed any mindfulness practice done well, evoke? Wherein does this mind body connection lie? Well consider this! You are walking down a forest path one dark and lonely evening. You come across a wild animal, say a cheetah. What happens? You are perplexed and frozen, your pupils dilate, nostrils flare, muscles tense, heart beats fast and becomes almost audible (palpitations), you start shaking, sweating and feel short of breath, you perceive a need to empty your bladder (or do so involuntarily), you feel as if you have run a mile. In short, unbeknown to you, your nervous system prepares you to fight or flee. This is the work of your Autonomic Nervous System, nerve pathways that exercise control over our everyday involuntary actions, even as we think and make important (voluntary) decisions, to talk, walk, climb, eat and so on.

This autonomous part of your nervous system (hence autonomic), which connects body and mind, is what is influenced by Yoga and mindfulness practice.

And be aware, it is intimately connected with the deep recesses of our brain, the oldest parts of our mammalian brains, the Limbic system, composed of the hippocampus, amygdala, insula, all of which have a role to play in memory and emotion. And the decisions, to fight or flee, to be aggressive or passive, are derived from the prefrontal cortex, to which the limbic system is intimately linked.

Thus, our ancients probably got it spot on when they described the kundalini and the practise of Yoga. When we practice Yoga, we influence the Autonomic Nervous System and through it the brain, thereby bringing about physiological changes, heart rate, blood pressure, breathing; mental changes, a reduction in anxiety and enhancement of mood and motivation; cognitive changes, improved attention and focus, enhanced memory and quite naturally behavioural changes, behaviour being the quintessential expression of emotion.

It falls upon us, therefore, to celebrate our ancients, who deduced all this without fancy brain imaging, neurophysiology and neuropsychology; who created perhaps India’s greatest export to the world, one that influences “the mindful neuron”!

* June van Aalst, Jenny Ceccarini & Koen van Laere. What has neuroimaging taught us on the neurobiology of Yoga? A review. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 2020; 14: 34

Dr. Ennapadam S Krishnamoorthy

MBBS, MD, DCN (Lond), PhD (Lond), FRCP (Lond, Edin, Glas), MAMS (India)

Founder: Buddhi Clinic